EDITOR’S NOTE: My cousin Jim Ostroff sent this to me a few weeks ago and asked me to post it here. Among other things, this page has become a repository for family information and memories. We both gave a lot of thought to the sensitive issues involved, and Jim especially came down on the side of sharing these at times painful family stories in the interest of truth.

Grandma Clara lived with us forever. Or so it seemed. Clara Skolnick Rosenblum, mom’s mom, was there—always there—tending to me and the twins, Matthew and Ellen. Grandma cooked and cleaned and got us dressed in the morning, as both mom and dad left early for work in the city.

Actually, grandma came to live with us in July 1953, when mom, dad and I moved from Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn to Douglaston, Queens, one of New York City’s five boroughs. The twins were born in October. We lived in a two-bedroom garden apartment, decidedly cramped quarters for three adults, two babies and a not-yet-three-year-old boy.

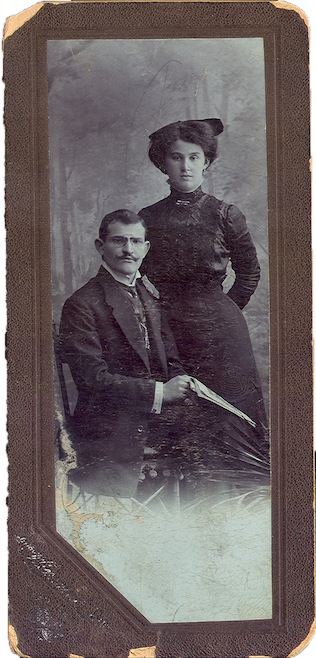

Jacob J. and Clara (Skolnick) Rosenblum, probably about the time of their 1910 marriage, and probably somewhere near Buczacz, Austria-Hungary.

Grandma Clara gave up her apartment in Brooklyn for reasons I never learned. Perhaps it was just time. Perhaps she no longer could cope, alone. Her husband and my namesake, Jacob J. Rosenblum, had been gone 10 years. The move out of Brooklyn came nearly 40 years exactly after Clara, Jacob and baby daughter Rebecca (later Virginia) left Austria-Hungary forever.

By the summer of ’53, all the daughters were long married: Virginia to Joe Altman, Charlotte to Phil Greenfield and my mom, Theodora, or Thea, to Herb Ostroff.

Perhaps grandma came to us by default. Virginia, Joe and Jay lived in a Brooklyn apartment, as did Charlotte, Phil, Lynn and Jeoffrey. Our Beech Hills garden apartment in Douglaston wasn’t much bigger, but my parents accepted her.

Moving to a three-bedroom apartment in the summer of ’54 made our lives marginally more comfortable. Grandma Clara slept on the living room sofa. All the rooms were small by today’s standards. There was one bathroom.

As a child it didn’t matter. That’s all we knew and most times all the kids would be outside playing some game on the street, or hailing down the Good Humor man. In winter, if I wasn’t out sleigh riding (sledding), sometimes I’d watch in the kitchen as grandma baked the most incredibly-tasty yeast-cinnamon pasty horns; sat rapt as she spun stories of her privileged childhood, the daughter of a wealthy brewer in Jazlowiec, Galicia, then part of Austria-Hungary, now Pomortsy in Ukraine.

Most times I was “Jimmy,” but many a time grandma would call me Yankele, after her husband. It was a heady mix, the swirls of yeast dough scents, bubbling chicken soup, percolator coffee and stories Grandma Clara would relate about growing up virtually a princess on a farm estate licensed by no less than the Court of Emperor Franz Josef.

The yarns grandma related about private tutors, servants, stacks of money in drawers, bulging bookshelves, miraculous folk remedies and being courted by a bevy of wealthy young men, were but fairy tales to a child who had just learned to read Andersen and Grimm, and even less believable.

One day, when I was about eight, I asked grandma why she insisted on telling me these stories. She covered a bowl of rising dough with a towel, sat down next to me at our small kitchen table and explained: “Yankele, I want that someone should remember who we are. I want someone to know where we came from,” she intoned in a thick, Germanic accent that rendered w’s as v’s.

Jim’s fourth birthday, Feb. 16, 1955. Left to right, Theodora “Thea” (Rosenblum) Ostroff, Jim “Jimmy” Ostroff, Clara (Skolnick) Rosenblum.

The seemingly enchanted existence crashed hard after Clara left the old country in March 1913. Life with Jacob and three girls in a Brooklyn tenement was trying. Though Jacob was a talented men’s clothing designer, with a degree from a prestigious Vienna school, the U.S. market for upscale men’s clothing makers was limited. His boutique store failed.

Jacob went to work in the schmatah trade, working long hours six days a week in a sweatshop, until the Depression made regular employment problematic.

Come the 1930s, Clara was said to have “nervous disorders,” a catchall for maladies doctors otherwise couldn’t diagnose. The doctors’ directives were similarly generic: go to the country for a few weeks in summer.

Somehow, they did, perhaps with the help of family. Photographs were a luxury and there are few of my grandparents after they posed for the obligatory ones upon arriving in America. An early August 1943 snapshot shows Jacob reclining on an Adirondack chair somewhere in the Borscht Belt, looking worn and beaten down at age 55.

Jacob collapsed at home two weeks later. The family doctor was summoned. He diagnosed a heart attack, but could do nothing. Jacob J. Rosenblum soon breathed his last, but not before murmuring, “I don’t care anymore.”

By the time Grandma Clara came to live with us in ’53, her medical problems mounted. As so many in her Skolnick family, she had heart disease. I recall times I walked with grandma about one mile “down the hill” to a local shopping area. Invariably, she had to stop and put a tiny pill under her tongue. Once, I asked grandma what she was taking and the answer shocked me. “Nitroglycerin,” she said. This greatly troubled the mind of a seven-year-old. I thought she’d blow herself up.

There were many other things I didn’t understand. Grandma Clara talked about having severe pains in her face. Grandma told me she got “nerve blocks” from doctors, administered via “long needles,” which she said was why her face drooped.

In the summer of ’59 grandma left us for several weeks. I thought that she went to live with Aunt Charlotte, Uncle Phil and my cousins, who had just moved to Syosset, Long Island, N.Y.

I did miss my grandmother and persisted in asking where she was, always getting puzzling non-answers from my parents, maybe the best they could do with an eight-year-old. One day they took me to see grandma, except I was not allowed to see her.

We drove about 20 minutes to a state mental hospital, Creedmore, located at the city line between Queens and Nassau County, L.I. If ever there was a place out of a nightmare, this was it. Thick bars girdled windows of the squat buildings. Huge trees overhung every inch of ground, bathing everything in shadow. Not a ray of sunshine.

Mom and dad said they were visiting grandma, but I couldn’t. Each took turns waiting with me in a lobby area that was open to the wards. It was a dark expanse with walls painted a drab brown-green. A white-uniformed woman sat at a desk. She gave me chocolate Tootsie Roll pops. One went in my mouth; the other two in a pants pocket.

I did not know of Bedlam, but this was a close approximation. People ranting, howling, screaming. Others drooped limp in wheel chairs, or flailed away in spastic hand jerks. The air was permeated by a urine scent.

I could not get out of there fast enough. When we finally did, I threw away the chocolate Tootsie Roll pops and never again could even look at one.

A week or so later grandma came home. I was told not to disturb her because she needed to rest. Showing an inclination that perhaps foreshadowed my career as a reporter, I kept asking questions, especially about why grandma wore a kerchief.

My mom told me but it didn’t make sense. Something about grandma being shocked. Years later I surmised that she likely underwent ECT at Creedmore.

No one attempted to explain any of this. Perhaps my parents thought it would be too much for a child to understand, or maybe they wanted to shield me at a young age from life’s harsh realities.

All I knew was that Grandma Clara loved me, would tell me endless stories and would take endless pills. I remember bottles and bottles of pills she’d keep in an old purse and that the walks on which she’d ask me to accompany her to the Deepdale pharmacy increased in frequency as the ’60s wore on.

So, too, did the times she’d sleep during the day, or frantically scrub the kitchen floor or wash down the walls.

Vague but distinct memories, as well, of my grandmother, who was very soft spoken, yelling at times on the phone. I didn’t understand the snippets that I heard. “Doctor! Pills, more. Need. Now!”

I never knew what grandma took, but thought she must be really sick, because by early ’63 she asked me to pick up prescriptions from the pharmacy when I got home from school. I did not understand why she didn’t walk there and back as she used to, or wait for my parents to come home from work at about 6 p.m.

Grandma explained that I could “run fast” and she needed the medication. Though just 12 at the time, I began to have an inkling that Grandma Clara—this proud, educated, smart, multilingual woman—had spiraled into drug addiction, abetted by doctors.

No one should take umbrage at the retelling of this human descent. Grandma was not weak of character or spirit. Nor did she intentionally seek refuge in mind-numbing pharmaceuticals. Her experiences are far more an indictment of a time and a system that marginalized women, attributed a bevy of ailments to “female hysteria” and wantonly prescribed drugs with no regard to their dangerous effects. Grandma Clara was one of a countless number of victims.

The departure

Late October ’63. It was a little before 5 p.m. Another boring session of Hebrew school was nearly over when my friend Harlan came in the classroom, said something to the teacher and then rushed over to me. Grandma Clara was very sick and I had to come home. We both ran six blocks down the steep hill to the apartment, where Harlan’s family lived upstairs from mine.

What I came home to was beyond the ken of a 12-year-old. Grandma was greatly agitated and super-hyper. She was talking a mile a minute. It was all gibberish. I was scared.

My younger brother and sister, Matthew and Ellen, were home. They were very scared.

All I could think of was that this was something out of a horror movie about aliens possessing humans. Was it a disease? Would we catch it and go crazy?

Our parents got home about 6 p.m., but it seemed forever.

Mom and dad took grandma into their bedroom and this is the only time I ever remember my dad screaming.

I never learned what had happened to Grandma Clara, what seemingly possessed her. I suspect that she inadvertently took an overdose of some amphetamine or other drug that caused her to be wired.

Grandma was her old self the next morning, but my parents stayed with her. When I returned home after school grandma was not there. My dad told me he had taken her to stay with Aunt Charlotte and Uncle Phil at their home in Syosset. Made sense. Grandma had stayed with them for a week or so a couple of times a year.

Weeks went by and she hadn’t returned to us. I asked if we could visit grandma in Syosset. My mom said we could not, because grandma wasn’t there. My understanding, gleaned from talking with my mom and relatives long afterwards, is that Aunt Charlotte committed her mother to Pilgrim State Hospital in Brentwood, Long Island.

The dream

A few days later my mom told me of a dream that had awakened her that morning. Mom said she was in an abstract, formless place. There was total silence. She looked up and saw her mother, Grandma Clara, standing slightly above her.

I remember distinctly sitting at the kitchen table as my mother related that she called, “Ma. Ma!” There was no reply. Grandma spoke no words, my mother said, but extended her left hand and showed my mother a white, square card.

Grandma tilted the card and on it was written 10. She rotated it a quarter-turn to show 26.

My mom related, in her dream, “Ma, what are you trying to tell me? What is it? What does it mean?”

Mom said that grandma remained mute, gazed intently at her and then vanished, prompting mom to wake in a sweat from this bizarre dream.

This was late October of 1963, a few days after grandma left us forever.

The puzzle

Mom had to figure out what it meant, for she was sure these were not random numbers. Though not very religious, mom believed the Kabalah were on to something; that there was a meaning to numbers if only one could discern their hidden meaning.

I well remember, though just 12 years old, huddling at the kitchen table with mom as she wrote out the numbers, arranging them in different combinations to find “something” that would have greater meaning.

She added the two numbers: 10 + 26 = 36

She added the constituent integers: 1+ 0 + 2 + 6 = 9

Mom tried adding the first and the last two, individually: 10 + 2 + 6 = 18

Mom thought she might be on to something when she added up all three possibilities: 36 + 9 + 18 = 63.

She tried other combinations, such as reversing the numbers: 62 + 01 = 63

Both ways she came up with 63, which was the year of the dream. So?

I recall her saying maybe the numbers 36 and 18 meant something reversed: 63 and 81. Nine is the same either way so perhaps it didn’t count.

Still, none of the numbers or combinations seemed to mean or point to anything, so mom tried a completely different approach.

Perhaps 10 26 should be thought of as 10 to 6, as in 10 minutes to 6 o’clock, or 5:50. Dad had been trying to get a job with a company at 550 7th Ave. Could this be a sign that he’d get it?

This seemed farfetched, even for a dream. She again focused on the numbers, looking for a pattern.

Mom came to think that somehow, the 9, 18, 36 numbers all were linked to 18. The number 18 has a special significance in Hebrew, as it is synonymous with חַי —Chai—life.

Mom didn’t ask Grandma Clara about this the last time that she or I saw her. It was July of ‘64. Mom and dad, along with Aunt Virginia and Uncle Joe, visited grandma at Pilgrim State. She was in no state to talk.

Grandma Clara seemed drugged up. I went to grandma to give her a hug. “Yankele, do you have cigarettes?” she said in an urgent tone. Huh? “No, grandma, I don’t smoke!” I said, asking her why she wanted cigarettes, since she never did. “For the nurses so they’ll be good and won’t hit me.”

Grandma Clara died the next month of pneumonia, I was told. She was buried next to her beloved Yankel in the Rosenblum family plot, Beth David Cemetery, Elmont, NY. Over time, I came to learn that everything that grandma told me—all those seeming fairytales—were true.

Mom’s efforts to interpret that dream, to find some significance in it, to find meaning in 10, 26, 18, 81, 36 and all the other combinations, came to naught. Eventually, she dismissed it as nothing more than a bizarre, meaningless nocturnal mash-up.

My dad didn’t get that job at 550 Broadway.

Still, for years dad would place small bets on the Irish Sweepstakes and later with New York’s Off Track Betting and the state lottery, using combinations of the dream numbers every which way. I don’t think he ever won a dime.

Questions

Years later, after mom died, I helped dad with the very difficult task of getting everything in order: collecting my mom’s clothing and shoes for donation, and helping him with paperwork.

There were scads of paperwork related to everything from her job with NYC’s Police Civilian Complaint Review Board, to St. John’s University, where mom was nearly done with her PhD, 9 years after she started college, taking night courses after work.

There were many long-time friends to be notified and acquaintances, such as John Lindsay. Mom wrote to Lindsay often when he was New York’s mayor and for years afterwards at his legal practice. Lindsay always replied, including to me in a condolence letter after mom’s passing.

Virtually everything had to be written out as an original. I couldn’t bring myself to use the typewriter on which mom had for decades churned out letters to family and friends and on which she worked, pro bono, as a consumer advocate for other people who had problems with products or services.

I filled out the forms, hour after hour, until my hand hurt. To save time and my hand muscles, I began to abbreviate the required information. Home address: 57-56 244 St. Employer: NYCPCCRB. DOB: 1/5/19. DOD: 10/26/81.

10 26. A shiver went through me….

What do I make of this? Nothing.

I think that if we look for numbers, for combinations, we will find them. In my life 222 has cropped up often. Grandma Clara was born February 22, 1892. Mom and dad were married Feb. 22, 1942. I was Bar Mitzvahed on Feb. 22, 1964, my parents’ 22nd anniversary. Wendy and I met on Feb. 22, 1975. Our Arlington home zip code is 22206.

All of these are simply coincidences with no greater meaning.

Besides, I couldn’t live my life thinking that there is a power that determines our future, our fate, our very lives. External forces can affect us, but it is by our actions, decisions and choices that our lives are roughly hewn.

That mom died on 10/26 in ’81, nearly 18 years to the day after grandma came to her in that ’63 dream must be a coincidence. It has to be. Right?

“There are more things in heaven and earth… than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

—William Shakespeare

Comments on this entry are closed.

FACINATING STORY I WISH I COULD WRITE AS WELL WE NEVER TAKE THE TIME TO RELATE OUR FAMILY HISTORY TO OTHERES FOR POSTERITY

Thank you, Morris, for your kind words. Each of us has unique stories of our growing up years; the people and events that shaped our lives. In truth, we are the stories we tell….