EDITOR’S NOTE: Jim Ostroff and I are second-cousins. We share the same great-grandfather. But because of the small-town nature of the shtetl, our family trees are more like vines intertwined at multiple points. My grandmother was a sister-in-law of his grandfather, so there’s the first degree of intertwining. His grandmother and my grandmother were also best friends, so there’s a vine that doesn’t show up on a family tree because it involves emotion but no DNA. Though Jim and I have spoken regularly over the last 60 years, he mentioned to me in a phone conversation a few weeks ago this bit of family lore that I’d never heard before. I was so impressed by it that I asked him to write it down to preserve it.

Clara Skolnick, probably about 1907, when she was 15, in a photo studio in Buczacz, Austria-Hungary.

She was a Princess.

The most beautiful, well-educated and world-wise woman in her small town.

As Klara reached adulthood, she was courted by a bevy of gentleman suitors — refined, educated and suitable to marry a woman of her standing: the daughter of a wealthy brewer, acknowledged far and wide for his razor-sharp intellect and integrity.

Possessed of a yen for equality rare for a man born in the mid-19th century, Chaim Shulum Schkolnik was adamant that Klara, born 1892, as her older brothers Folic and Paul, would receive a first-class education.

Private tutors called upon the family home, surrounded by fields of hops and grains used to make beer at the on-site brewery. It was constructed by Shulum, who was said to have earned an engineering degree, on the outskirts of a small town. With about 500 people, Yazlivitz, or Jaslowiec in Polish, was a backwater shtetl in Southeast Galicia, a province of Austria-Hungary, today known as Pomortsy, Ukraine.

The three schoen yingele (Yiddish for “beautiful children”) were schooled in literature, history, mathematics, science, the Jewish religion and culture; were steeped in the ethics of Torah and Talmud, from which they read in Hebrew.

The lingua franca for instruction was a mélange, given that German, Yiddish, Polish and a Ukrainian dialect were spoken throughout Galicia.

Their homestead provided ample room for classroom instruction. It was a manse, unlike the cramped, thatched roof cottages that were home to most area residents, with a separate kitchen and indoor plumbing, a rarity. Ukrainian servants attended to the family’s needs.

Clara Skolnick in another studio portrait, sometime in her late teens, in Buczacz, Galicia, Austria-Hungary. (Collection of Jim Ostroff)

Unheard of in shtetl homes, the Schkolnik’s boasted a library of secular and religious texts, including a High Holiday machzor, prayer book, that Shulum’s wife, Surah Henya Strober, had received as a gift in the late 1860s.

The family’s financial well-being was tangible. “You could pull open drawers and find stacks of money and my mother had boxes filled with her jewelry,” Klara said years later.

Klara noted her father “never made a show” of their wealth. He emphasized doing so was wrong, explaining, “You never should do anything that might shame another person.”

The Schkolniks were adamant their daughter would be adept in the social graces. Klara recalled being schooled in the proper dress, bearing and manners for a woman of high standing; of being taught the polka, Ukrainian folk dances and most especially the waltz.

Though religiously observant, Shulum did not subscribe to the practice of arranged marriages, common among the era’s Jewish families.

Young gentlemen of the proper standing would be permitted to call upon his daughter at home. Should Klara wish to wed, though, Shulum would need to assent.

Beginning in early 1907, when Klara was 15, gentlemen visited the Schkolnik home, each signing a book she kept, akin to an autograph album.

Likely in 1909, when Klara was 17, she met Jacob Jeremiah (Yaakov Yerichim) Rosenblum, who recently had graduated from the Menschneider, then a prestigious Vienna men’s apparel design school.

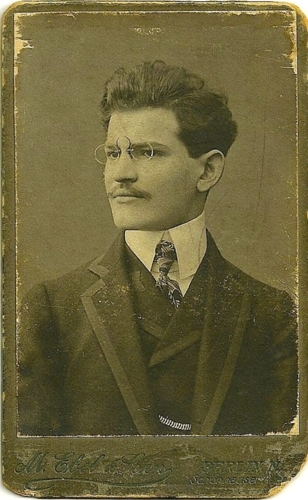

Jacob J. “Yankel” Rosenblum in Vienna, Austria, while a student in a prestigious men’s apparel design school, in the middle of the first decade of the 20th Century. (Collection of Jim Ostroff)

Details of their courtship are murky, but Klara recalled falling deeply in love with Jacob, whom she called by his Yiddish name, Yankel.

Early in 1910, when Klara turned 18 and Jacob was around 22, he proposed marriage. Klara broached the subject with her father.

Shulum was repulsed. It is not known whether he had spoken with Jacob, but the reputation of the Rosenblum family, from nearby Buchach, was known to Shulum.

Jacob’s father Avrum and his grandfather Oizer, were not held in high regard, with both said to be of questionable character and integrity. Word of mouth had it that Avrum’s carousing prompted his wife, Bobscha Tepper, to divorce him, though they later remarried.

No matter young Jacob’s character and schooling, this man was not suitable to marry Shulum’s well-educated, cultured belle, who had been courted by men of substantial means and sterling reputation.

Klara and Jacob together made an appeal to Shulum, a talk made more difficult as he was ill with “galloping consumption,” a term then used to describe a wasting, terminal disease.

It was said that Shulum, a heavy smoker, developed lung cancer, and was given morphine to ease his pain.

Perhaps Shulum was under the influence of narcotics when Klara and Jacob sought Shulum’s blessing for them to wed.

This was not forthcoming. Shulum became angry, Klara related years later, telling the young couple, “If you marry, I curse you for the rest of your lives. You will never know happiness.”

Shulum soon died and within months, Klara and Jacob married. Jacob’s grandfather Oizer, who served as a notary and an official recorder of documents, witnessed their religious ceremony.

Jacob and Clara (Skolnick) Rosenblum, probably soon after their 1911 marriage in Buczacz, Galicia, Austria-Hungary. (Collection of Jim Ostroff)

Soon thereafter, Klara traveled with Yankel to Vienna, where they “danced the night away” to Strauss’ Blue Danube waltz, their mutual favorite, she recalled.

Klara loved Vienna for its high culture, nightlife and a fastidiousness for cleanliness, noting “there was not a speck of dirt anywhere. You could eat off the streets.”

Klara and Jacob Rosenblum settled in Buchach where in November 1911, a daughter Rebecca (later Virginia) was born.

The family was intent on immigrating to the United States, but could not until they had a legally recognized civil wedding – which they did in 1912 – and documents attesting to these nuptials were filed with Austria-Hungary.

Oizer balked several times, demanding an escalating fee. With money in hand, Oizer notarized the civil “wedding bann” document in March 1913. Within days, the Rosenblum family sailed for the U.S., living for several months with Klara’s maternal uncle and aunt, Mendel “Max” and Nellie Struber in Williamsburg, Brooklyn.

The Rosenblum family moved into their own apartment on South 2nd Street, Williamsburg, but domestic life did not much suit Klara, now Clara.

In the teens, she became politically active in the women’s suffragette movement and by 1918, took to street corners protesting the U.S. entry into World War I. Her anti-war harangues in heavily German-accented English did not go over well with crowds. She was pelted with tomatoes.

Two other children came along: Theodora (“Thea”) in 1919 and Charlotte (named after Shulum) in 1924.

Jacob and a partner, Jacob Wolfthal, established a custom-made men’s suit manufacturing business. It thrived, but went under in the midst of the Great Depression.

To provide for his family, Jacob worked punishing hours in New York’s garment center. Though financial security remained elusive, Jacob was beloved by family for his sharp wit, humor and personal integrity.

Though he evinced a buoyant personality, by the 1930s Clara was beset by physical and emotional ailments, which doctors ascribed to “female hysteria.”

Jacob suffered severe chest pain one morning in August 1943. A doctor summoned to their Flatbush apartment diagnosed a heart attack, but could do nothing. Jacob’s last words, according to Thea, who stopped by on her way to work: “I don’t care anymore.”

Clara lived on in Brooklyn until 1953 when she moved into a Queens, New York, garden apartment with Thea, her husband Herb Ostroff, and their three children.

Clara’s ongoing medical ailments mounted. Severe facial pains were remediated with “nerve blocks” that left one side of her face permanently drooped. Clara also underwent electro-convulsive shock therapy at Creedmore State Hospital.

Prescribed mind-numbing drugs, she spiraled down into drug addiction until one day in October 1963, the cocktail left her in a manic, frenzied state that scared the daylights out of the three children.

Thea prevailed upon her sister Charlotte to have Clara live with her family on Long Island for a period.

Clara stayed with them for several days before Charlotte committed her mother to Pilgrim State Hospital in Suffolk County, Long Island.

Clara died there of pneumonia 10 months later. She was buried next to Jacob at Beth David Cemetery, Elmont, Queens.

Clara loved Yankel until the day she passed on, but throughout their lives together, neither knew much happiness, contentment or peace.

EDITOR’S NOTE: James J. “Jim” Ostroff (Yaakov Yerichim, Yankele) is the son of Herbert and Theodora (Rosenblum) Ostroff and a grandson of Jacob and Clara (Skolnick) Rosenblum. He is a great-grandson of Chaim Shulum and Surah Henya (Strober) Schkolnik, and of Avrum and Bosbscha (Tepper) Rosenblum. To see Jim’s other essays on our families, see here and here.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Great, great story, Jim! Thanks for sharing it. Tell me: why did Rebecca go by the name Virginia?

Many thanks, Lisa, for your kind comments about the recollections and anecdotes regarding my grandparents, their times and our ancestors-in-common.

Jacob’s and Clara’s first child, born 11/11/11, was given the Hebrew name Rivkah. For the purpose of birth registration, she was given a “civil name”:Rebeka, which in the U.S. was spelled as Rebecca.

Around the mid-1920s, Rebecca decided to adopt what then as now could be termed a more “hip” name. Rebecca became Regina.

Towards the late ’20s, deep into the Flapper Age, Regina adopted an even hipper nickname: Reggie.

By around the mid-1930s, Regina decided to change her first name again, to Virginia.

But…, to family and friends, she was known as Ginny.

We need to keep in mind that during these decades, before background checks and even Social Security, individuals could easily adopt any name that suited themselves.

My mom was named Tilah Etel and given the English name Theodora, which is of Greek origin. Go figure! Well, our Schkolnik grandparents were versed in Greek.

When Jacob Rosenblum received his Naturalization papers in 1926, he listed his/Clara’s children’s names as Regina, Tillie and Charlotte.

My mom was called Tillie by family members. For decades, she went by Thea and late in life, as Theo.

Surnames could be “flexible,” as well. My mom, as Theodora Rosenblum, had difficulty finding work as a legal secretary. As Theodora Ross “that issue” was mitigated.

Charlotte (named after Shulum) always was Charlotte. Except when her antics were too much for her father. “Charlotte-tsuch”! This appellation defies an easy translation, but knowing Charlotte as you did, you get the drift.