I could tell it was from overseas because of the long string of digits in the Caller ID box. I understand that technology has advanced greatly since my youth when an overseas phone call was less common than a man walking on the moon. Still, I don’t get many overseas calls.

The caller was a woman who identified herself as “Stavi.” It took me a couple seconds to figure it out. She was Zipora (Ehrlich) Stavi, a Strober relative I’d emailed early last month to see if we could share some genealogy information.

Zipora Stavi, a former school teacher, gemologist, and realtor, in Tel Aviv, 1995

Stavi, as she prefers to be called, shared one gem right off the bat: that her great-grandfather, currently identified on our family tree as UNK Strober 1215, was actually named Elyakim Getzel Strober (after King Hezekiah’s emissary described in II Kings 18:18. If our other information is correct—and that’s a very big if—Elyakim Getzel would have been born sometime around 1820.

Her information is one more clue in figuring out how the two big branches of the Strober family, now numbering more than 1,200 names on the family tree, may be tied together. It’s one more clue, but it’s not yet the final one. The common progenitor of my side of the family was Abraham Aaron Strober, born (we think) between 1797 and 1808. We’re not sure who is the common progenitor of the other branch of the Strober family, but it comes down to whether that branch was descended from one of Abraham Aaron’s son, or the son of one of his brothers.

So the math works like this: if Abraham Aaron was born in 1797 and Elyakim Getzel was born in 1820, it’s possible they were father and son. If, on the other hand, Abraham Aaron was born in 1808 and Elyakim Getzel was born in 1820, it’s not likely they were father and son (Abraham Aaron would have been 12 when Elyakim Getzel was born). There’s something else here: there’s no Elyakim naming pattern in my branch of the family. If he was a patriarch, we can assume some children born after his death would have been given his name.

But we know from DNA testing of several people on both sides of the family tree that there’s a definite genetic link. We still can’t pinpoint the person who provides it.

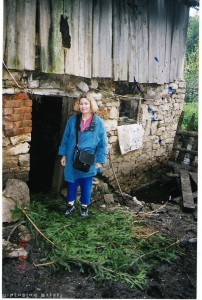

Zipora Stavi on the farm in Silo Rublino, Tarnopol Oblast, Ukraine, showing the entrance to a spot her family dug beneath a pigsty and in which they hid for most of World War II.

Though I hadn’t spoken to Stavi before, I had read about her quite a bit. She provided an oral history some years ago to the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw that tells the harrowing tale of how most of her immediate family survived World War II through the kindness and faith of a Catholic farm family outside Buczacz in what is now Ukraine. She told me the story of wartime salvation continues to this very day and was documented in an article in the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz.

I look forward to my next phone conversation with Stavi, and to the parcel she said she mailed me detailing much of the genealogy of her branch of the family.